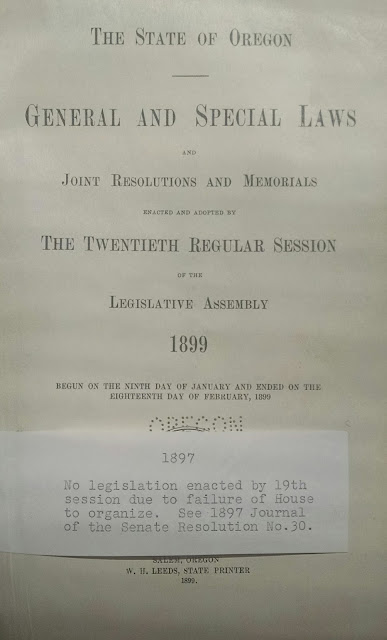

While looking through Oregon Session Laws I came upon this

strange note.

It immediately piqued my curiosity and I looked up 1897

Senate Resolution No. 30 to get the story – which turned out to be unexpectedly

rife with scandal.

The Oregon Senate verbally castigated the House for failing

to reach a quorum and declared that no business could be conducted. It

dissolved itself in a huff and blamed the “high-handed and revolutionary

tactics” of the house for the lack of legislation. What could have so upset the

politics of Oregon that the House refused to convene? The resolution and it’s

mention of the election of a United States senator brought to my attention the

astonishing episode of John H. Mitchell and the Hold-Up Session.

[John M. Hipple aka John H. Mitchel Library

of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cwpbh.04276.]

John H.

Mitchell was born John M. Hipple in 1835 in Pennsylvania. In the 1850s, after

graduating from college, he worked briefly as a schoolteacher. During this

employment he impregnated one of his students, the 15-year-old Sadie Hoon. They

were quickly married and had two children. By 1857 he had established himself

as an attorney in a local law firm. Apparently dissatisfied with his life in

Pennsylvania as an attorney, he absconded with $4,000 from his law firm, left

his family and took his new mistress to California, where she soon bore a

daughter. However in 1860 he tired of the Golden State, and abandoned his

mistress to travel to Oregon with their daughter.

Having

arrived in Oregon, our hero now styled himself John H. Mitchell. He shortly

married a local woman without having obtained a divorce from his first wife,

Sadie. However, charges of bigamy did not seriously impede his public life in

Oregon. In the midst of all this and other chicanery, the currently styled John

H. Mitchell secured three terms in the United States Senate; one from 1873 to

1879 and two more from 1885 to 1897.

If you remember

the note that first brought Mr. Mitchell to my attention, the date of 1897

should stand out – it’s the year that the Oregon house refused to convene.

Mitchell was now about to become the cause of the Hold-Up session! In 1897 U.S.

Senators were appointed to the senate by the state legislature. (Direct

election of U.S. Senators wouldn’t come about until the 17th

amendment in 1913.) So in 1897 Michel’s reelection was an issue for the Oregon

State legislature. Naturally, you would think that the legislature balked at

reelecting Mitchell based on his sordid personal and professional dealings. You

would be wrong!

The

real reason for the Hold-Up was money, not the poor morals of Mr. Mitchell. The year 1893

had seen a major financial panic. In 1896, Republican William McKinley rode

disaffection with the Democratic leadership to the White House. As part of his

campaign, he favored a gold standard for the currency and

rejected Democratic calls for a looser silver currency. Senator Mitchell after some prevarication backed

his party’s calls for a gold standard. In Oregon, a combined majority of Free-Silver

Republicans, Democrats and Populists supported silver coinage. They saw silver

coinage and an expansion of the currency as a way to inflate their way out of

some of the debt that had piled up during the financial crisis of 1893.

Farmers, like those in Oregon, were frequently silver partisans as

debt was a fixture of their day to day business.

The Anti-Mitchell

free silver forces quickly assembled and acted. They collected the Free-Silver

Republicans, Democrats and Populists and accomplished the following:

By forming a credentials committee, the silver supporters

were able to outmaneuver Senator Mitchell. (Incidentally you may note the

inclusion of the young

progressive U’Ren who would later figure prominently in Oregonian

politics.) The credentials committee never intended to credential anyone. In

fact, the committee never reported at all. This was vital considering Article

IV Sections 11 and 12 of the Oregon Constitution:

Section 11. Legislative officers; rules of proceedings; adjournments. Each house when assembled, shall choose its own officers, judge of the election, qualifications, and returns of its own members; determine its own rules of proceeding, and sit upon its own adjournments; but neither house shall without the concurrence of the other, adjourn for more than three days, nor to any other place than that in which it may be sitting.—

Section 12. Quorum; failure to effect organization. Two thirds of each house shall constitute a quorum to do business, but a smaller number may meet; adjourn from day to day, and compel the attendance of absent members. A quorum being in attendance, if either house fail to effect an organization within the first five days thereafter, the members of the house so failing shall be entitled to no compensation from the end of the said five days until an organization shall have been effected.—

Thus, in the house, the pro-Mitchell forces could not win a

quorum to elect Mitchell senator, nor could the anti-Mitchell forces adjourn without the consent of the

Senate. This left the legislature in

a stalemate, and over the next weeks the Oregon legislature was unable to conduct any business.

The

legislative session was itself characterized by acrimony and sharp dealing on both sides. An

aborted attempt to bribe members of the legislature was recorded by Oswald

West, later the 14th governor of Oregon:

An amateur politician representing a wealthy Portland gentleman, with senatorial ambitions, thought he sensed a chance to set the ball rolling for his candidate. He gave a sum of money to a political associate who claimed he could land a couple of house members. This friend, not wishing to appear in the transaction, turned the money over to a temporary state house janitor (for the session only) for delivery to the two alleged prospects. The folding money looked so good to the janitor that he sunk it all deep in his pocket – peeling off just enough to buy a railroad ticket south.

This was all done without the knowledge or consent of Simon or Bourne. To make matters worse the amateur politicians swore out a warrant for the janitor’s arrest and had him returned to Salem where some of the money was recovered. The event, of course, gave the city a laugh. No one thought for a moment that any jury would convict a man who had decamped with money given him to buy two members of the legislature. The charges where, therefore, dropped – the janitor left free to walk the streets of Salem, and, by talking, make himself a political nuisance.

Although in no way responsible for this senatorial fiasco, the anti-Mitchell forces wished to get the janitor out of town – to stop his chatter. So, on a certain date, around about midnight, a messenger was sent for a Marion County man, who was asked to come to Bourne’s sleeping quarters in the Eldriedge block. Arriving there, he knocked on the door, and was told to come in. Entering the room he found Bourne, in his nightgown, sitting on the edge of the bed. In a chair near its head, sat Senator Simon. Bourne did the talking. He said he wanted that damn janitor taken out, and kept out, of the state, until after the adjournment of the legislature.

On the dresser, near the head of the bed, stood two of Bourne’s detachable cuffs. He reached and pushed one over – and out tumbled a roll of bills. He counted out what he said was $2,000 and handed to his visitor, stating that that should cover all expenses.

When he arrived home (as he told it to me) he found $2,100 in the roll. So, early in that day he rounded up the janitor, took him over to our neighboring State of Washington and, upon promising to keep going gave him $600 retaining $1,500 as his commission on the transaction. Thus ended another chapter of the hold-up session.

The end

result of all this political maneuvering was that no Senator was elected that

session. Governor Lord attempted to appoint a replacement for Mitchell’s seat but the U.S. Senate, responding to Mitchell’s influence, refused to seat

the replacement. Only in 1898 was Joseph Simon elected to fill the vacancy,

leaving Oregon short one Senator for two years.

Undeterred,

John H. Mitchell rallied and was again elected in 1901 to the U.S. Senate.

Despite his political difficulties he never slackened his drive for corrupt

dealings. Mitchell, among others, conspired to obtain and sell lands intended

for homesteaders in the Willamette valley to lumber companies. During the 1901

senatorial term he was convicted for his role in these dealings. This sad

episode was called Oregon

land fraud scandal. He was one of only five U.S. Senators ever convicted

while in office. He died in 1905 while that conviction was on appeal.

The

story of John M. Hipple, as his abandoned wife called him, or John H. Mitchell,

as he was known in Oregon, is comforting or discouraging depending one's outlook. It comforts by demonstrating that political corruption and

deadlock are not a modern invention. It discourages by suggesting that will remain a enduring difficulty. Either way it’s always a good idea to

keep a eye open for little notes tucked into books!

MacColl, E. K., & Stein, H. H. (1988). Merchants, money, and power: The Portland

establishment, 1843-1913. Portland, Ore.: Georgian Press.

West, Oswald (1950). Reminiscences and Anecdotes: Mostly

About Politics. Oregon Historical Quarterly,

51, 95-110.

No comments:

Post a Comment